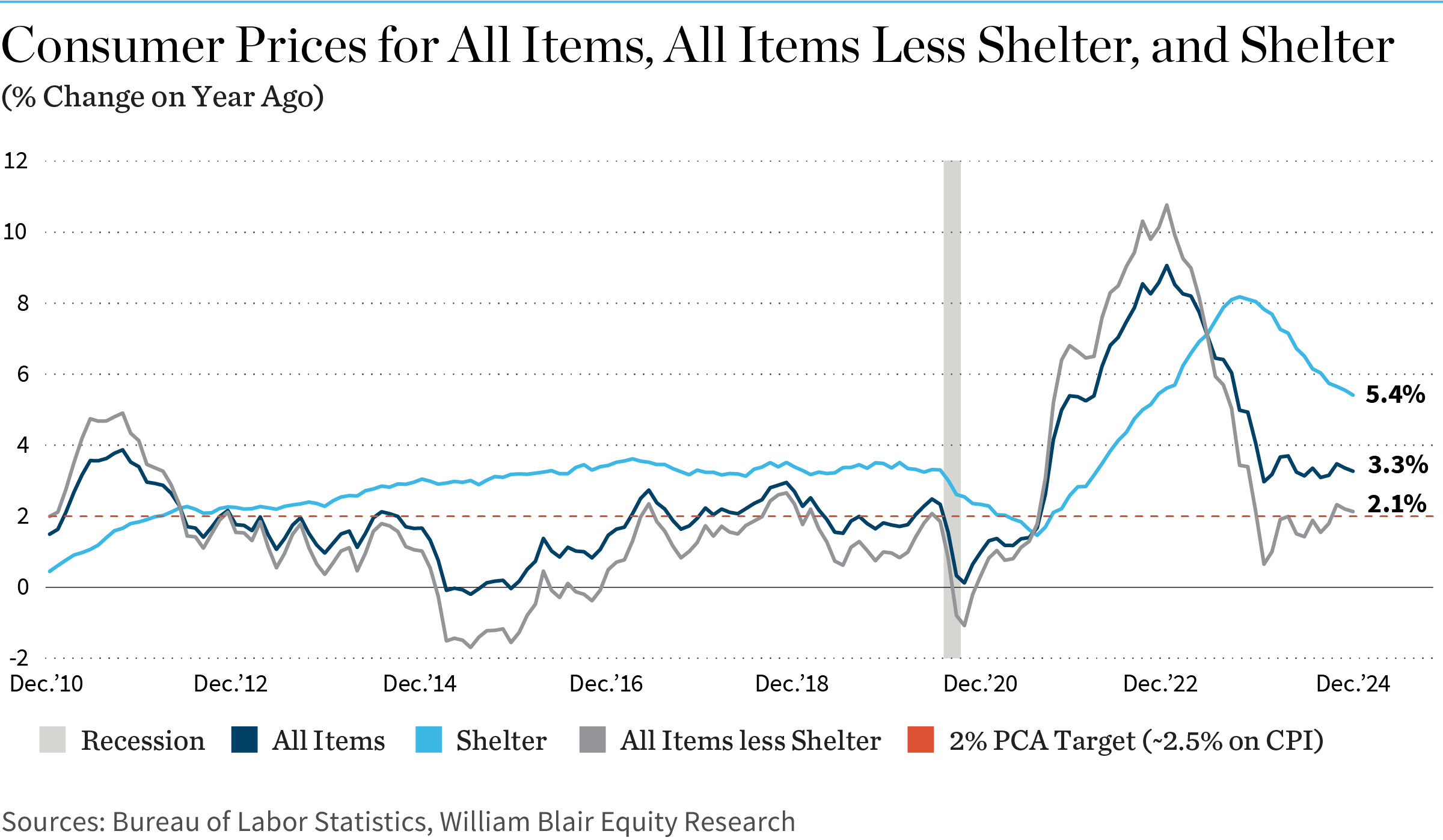

Rent inflation is, once again, becoming one of the stickier questions around the overall inflation conversation. Shelter accounts for 36.1% of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) basket, and shelter inflation was still at 5.4% in May. As such, it continues to be one of the most significant hurdles for the Federal Reserve to reach its 2% inflation target. In this Economics Weekly, William Blair Macro Analyst Richard de Chazal examines the shelter issue and where it’s likely to head over the next year.

As Exhibit 1 shows, if the shelter component were excluded from the CPI basket, inflation would currently be running at 2.1%, which is actually up from just 0.7% annually in June 2023. Getting a firm grip on where rental inflation might be heading is crucial for the Fed, as it’s keen to start lowering rates and get ahead of what could be a harder landing if its policy rate remains in highly restrictive territory for much longer.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) shelter component combines two major items: rent of primary residence (7.6% of the CPI basket) and owners’ equivalent rent (OER; 26.6%). The first is simply the monthly cost of renting a dwelling, including utilities, and the other is an attempt by the BLS to apportion the cost of owning a home—not home prices.

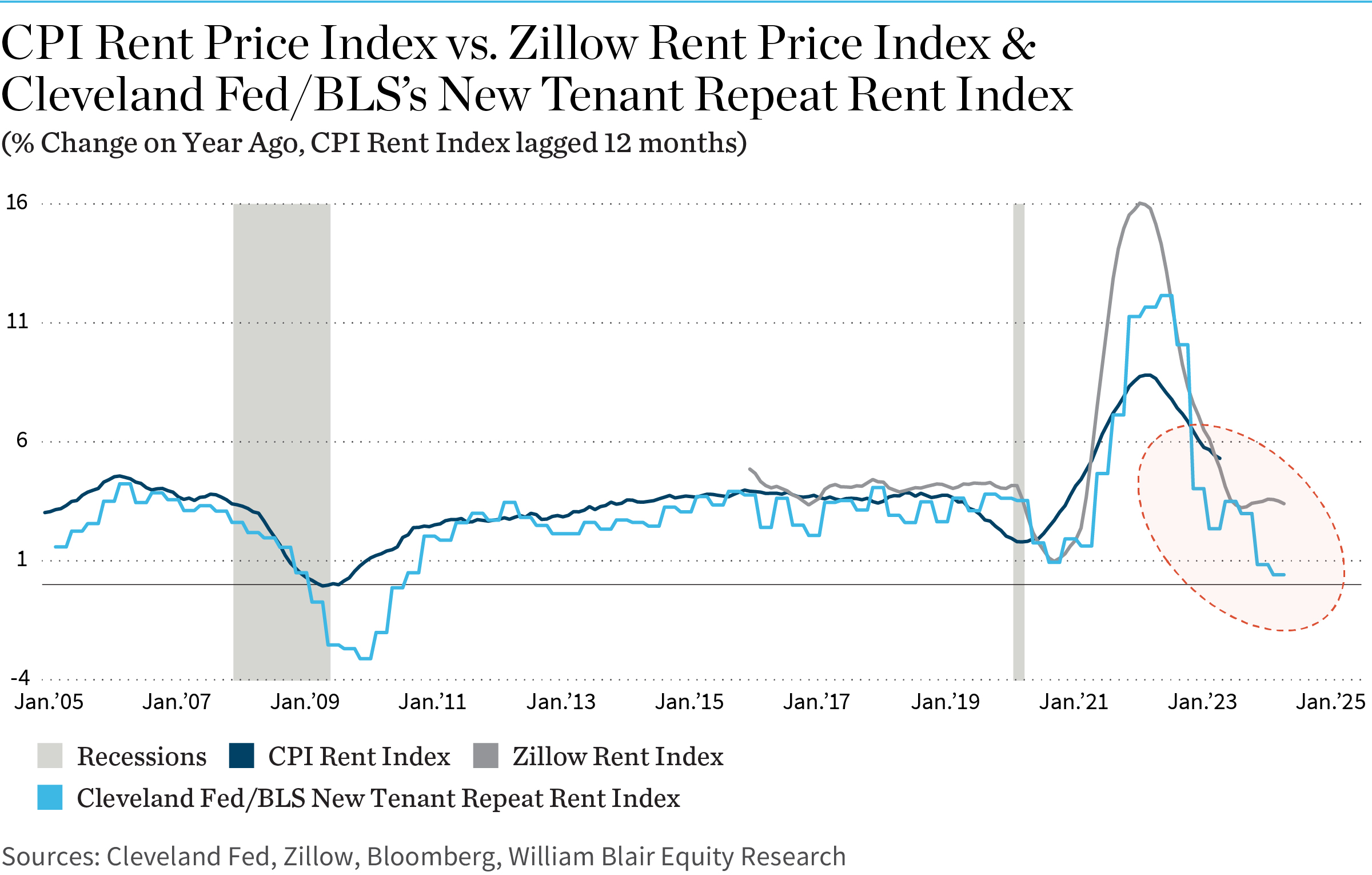

The important point to note here is that the BLS measure of rent includes rent for both new renters and existing tenants. This means the CPI’s rental price index does not exactly match market-based rental price indices, which only look at new rental prices. As a result, the CPI’s shelter price index tends to lag market-based rental indices by eight to 14 months. Looking at what’s happening with current market-based rental prices provides a good indicator of where inflation will likely be heading over the coming year.

Exhibit 2 depicts the Zillow Rental Price Index, as well as the BLS’ and the Cleveland Fed’s alternative New Tenant Repeat Rental Price Index (NTRR).

As the exhibit shows, the Zillow index points to prices continuing to decelerate steadily to around 3% by the fourth quarter of this year. The BLS’ NTTR index points to a much sharper deceleration to 0.4% by the start of the second quarter of 2025. While this latter figure is encouraging, the relatively small sample size for this data series leaves its result open to some skepticism.

There are two other more fundamental reasons we believe rental prices should continue to move lower over the coming year:

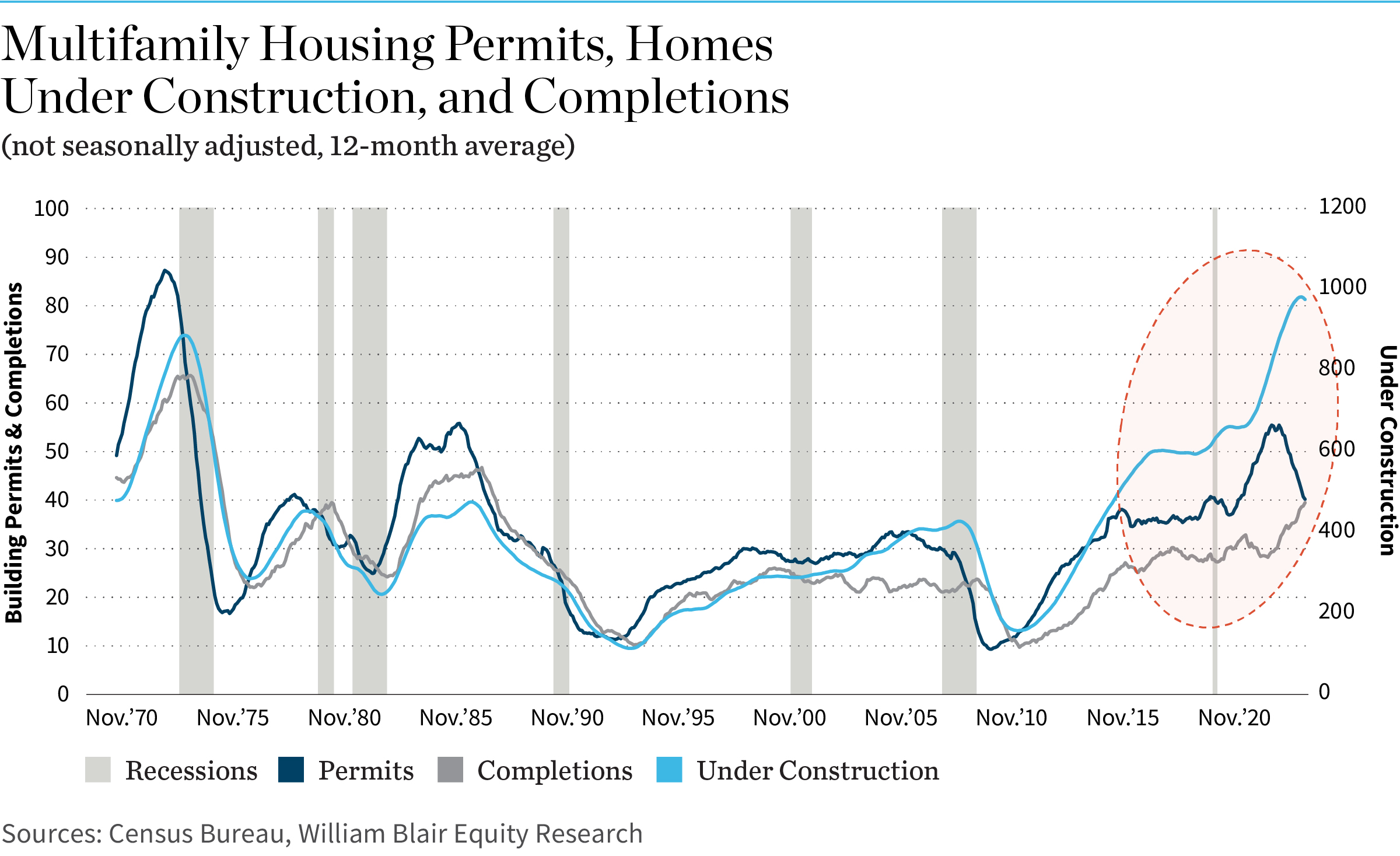

- The number of multifamily homes under construction still far outpaces anything we’ve seen before, as shown in Exhibit 3. This implies a significant increase of supply in the pipeline that homebuilders will likely need to shift at competitive prices.

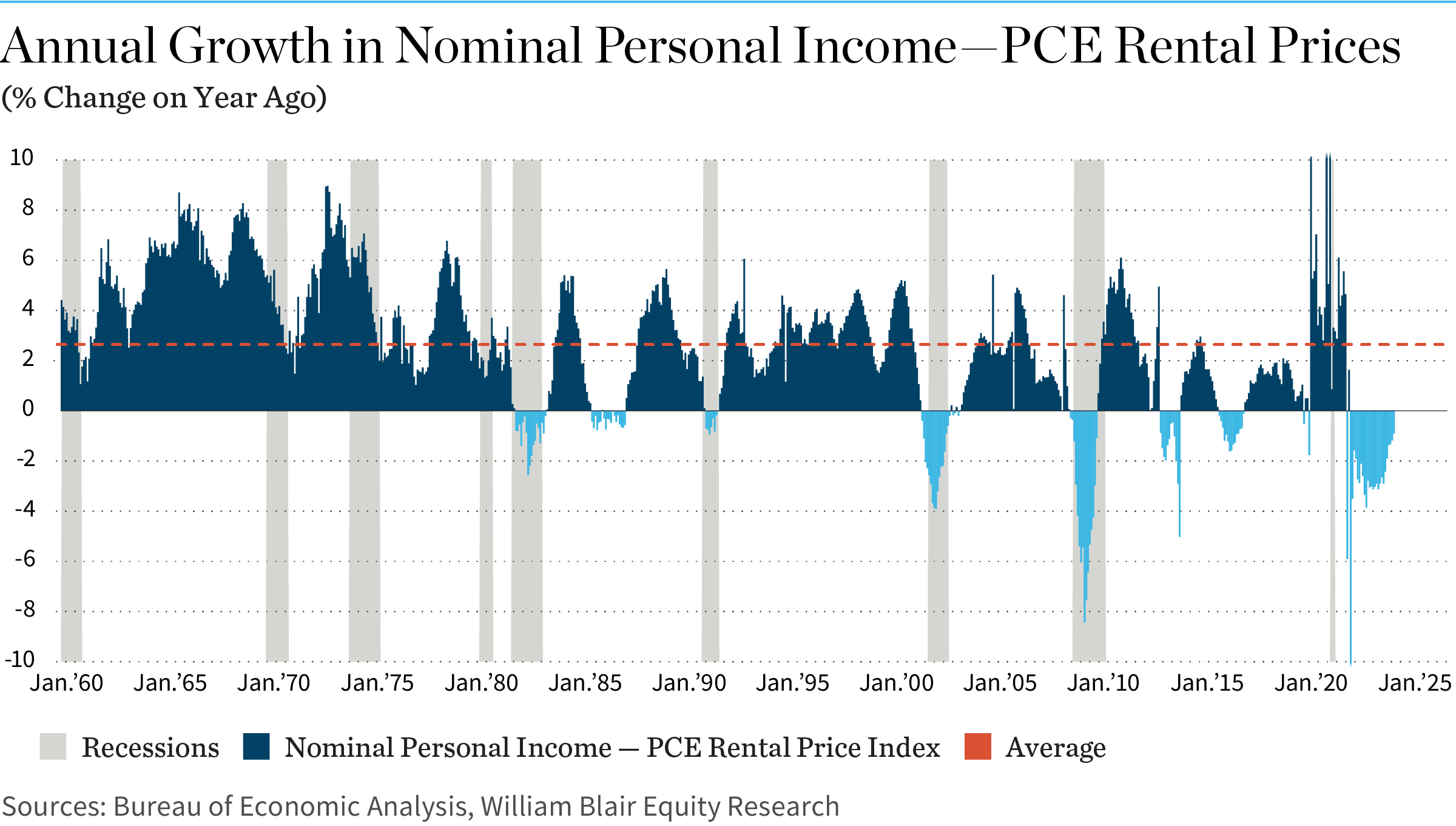

- Rental prices will continue to decrease because, over time, income has to rise faster than the pace of shelter inflation. Otherwise, many would find themselves homeless, and property owners would find themselves with empty buildings and need to cut rent to fill them.

Exhibit 4 shows the current divergence between nominal personal income and the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) rental price index. The differential is still -0.9 percentage points, implying that either wages will have to rise substantially, the prices of other non-rental goods and services will have to fall substantially, or the pace of rental price growth will have to come down. The historical average differential since 1960 has been 2.7 percentage points, and since 2000, it has been 1.1 percentage points.

The shelter component is the largest single component of the CPI basket, at 36.1%, and it’s still running hot at 5.4%. Where shelter goes, inflation often follows. The Fed will want a good indication of where shelter inflation is heading before it starts lowering interest rates. Looking at these market-based indices, we have a pretty good idea of where shelter and inflation will be heading in the coming year.

There are two reasons we believe shelter inflation is likely to decelerate over the coming years:

- A large supply of multifamily homes is in the pipeline, which will depress prices as they’re completed and brought to the market. This supply could be added if interest rates are lowered and existing homeowners decide to sell their properties.

- The growth of rental prices is far outpacing nominal income growth, which is not sustainable and can only happen for a limited amount of time before demand for those properties at those prices dries up as they become completely unaffordable.

For more information on the research reports published by Richard de Chazal, please contact us or your William Blair representative.