With the next Fed meeting still a few weeks away, we look at the recent messaging from Fed Chair Powell to decipher how they are trying to pull rate expectations higher and dissuade the market from prematurely pricing in a pivot.

There are three key factors that will dominate the investment landscape over the coming year. The first is the looming recession, the second is inflation, and the third is where interest rates end up. The latter necessarily will be dictated by the second. While there has been much written about the coming recession, what has been less clear is what the Fed is specifically looking for to assess whether it has done enough.

At its last FOMC meeting in December, the committee significantly increased the anticipated level of interest rates through 2023 and 2024. According to the latest dot plot, the Fed now expects rates to increase to between 5.1% and 5.4% in 2023, before falling to an even wider range of 3.9% to 4.9% in 2024.

However, these forecasts are somewhat at odds with what futures market participants are expecting. While the terminal rate expectations have increased over the last few weeks, they still suggest that the Fed’s peak rate will be just below 5%, at 4.97% (up from 4.86% at the last FOMC meeting). This peak in rates is expected to be reached in June, before the market believes the Fed will then start to swiftly cut rates by approximately 25 basis points in the second half of 2023, and a further 100 basis points in 2024.

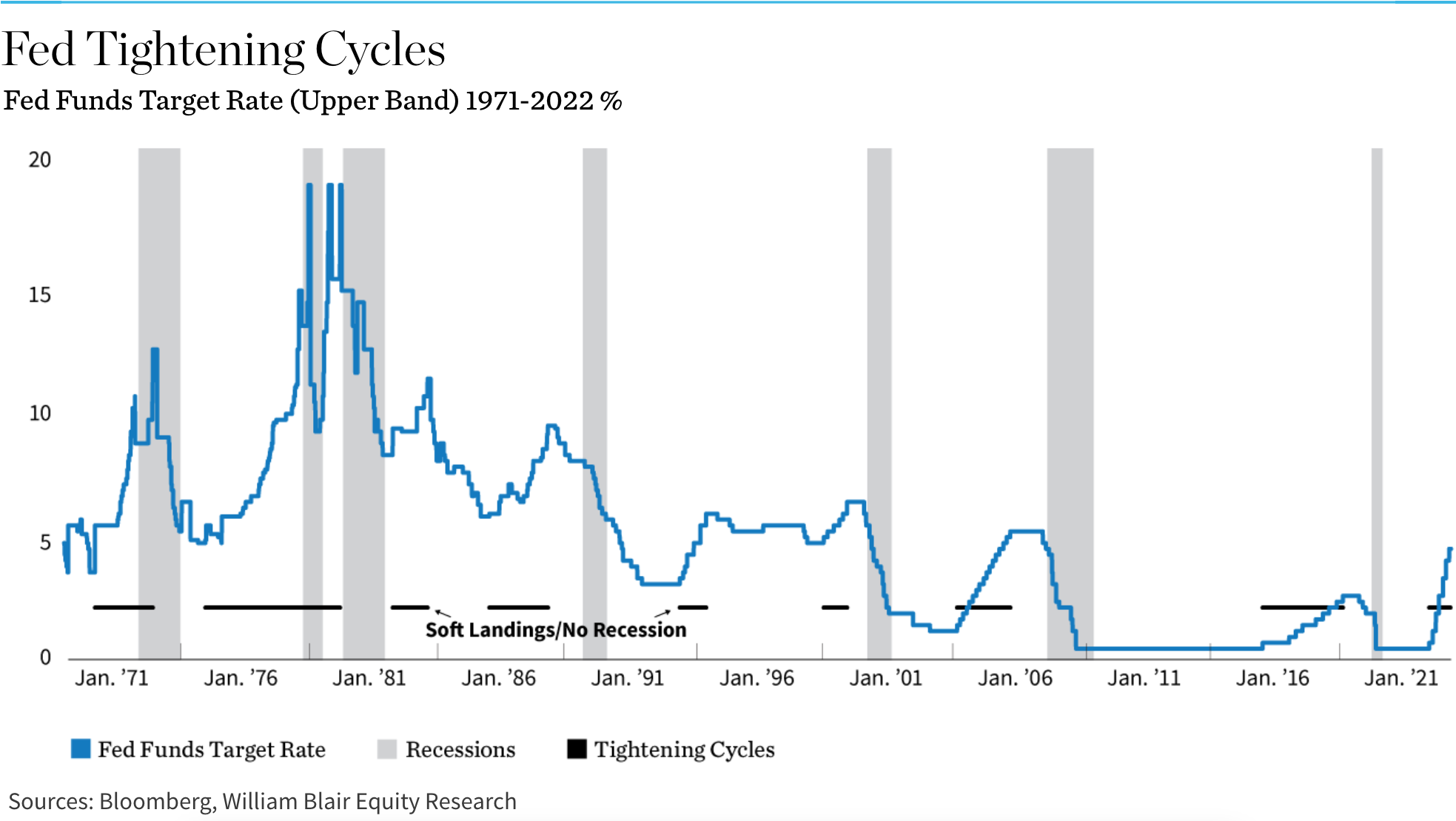

The following graph shows that such rapid expected rate cuts are not at all at odds with the Fed's past behavior, even though it is very much at odds with its current rhetoric. Since 1971, once the peak in rates has been reached, the Fed has only sustained them there for an average of 5.5 months before lowering them again. The longest they held them at this peak rate was in 2006, which was for 15 months.

Meanwhile, as the graph also shows, since 1981 there have been no instances when the Fed has continued to tighten policy during a recession. Furthermore, for those years where a soft landing was not achieved, the peak in the funds rate has tended to precede the start of a recession by roughly 13 months. The Fed has also typically even started to cut rates prior to the start of each downturn. Today, the Fed is cutting a much finer line. While it will likely end rate increases before the recession starts (assuming it starts in the second half of 2023), the Fed is very clearly telling us that we should not expect the agency to be as quick to lower rates as it has been in the past.

The Fed has recently been in a tug of war with financial market participants—one where it seems to have gained a little ground, though market participants remain skeptical. It believes that the lags associated with monetary policy taming inflation are long. And the longer inflation stays high in the interim, the greater the risk of both inflationary expectations becoming unanchored and of a wage-price spiral gaining traction.

The Fed believes that financial market participants have been prematurely pricing in a pivot and rate cuts (which would be consistent with historical Fed behavior), and thus unhelpfully easing financial conditions—the main channel through which monetary policy operates.

Powell admits that the Fed is still feeling its way around when it comes to knowing exactly when to stop raising rates; however, he has been quite specific in wanting to at least see: financial conditions tighter, some clear moderation in non-housing services inflation, and some broader-based weakness across the economy, most specifically in the labor market. Lastly, Powell has been clear that he wants to see all of these taking place on a sustained basis, and the Fed will not be quick to react to just one or two months of deteriorating economic data.

While there is a definite risk of the Fed overdoing it, the agency believes that it is far easier to signal future rate increases that can easily be scaled back in the future, than to find itself once again on the back foot having to raise rates much higher and faster than previously anticipated.