With the year-over-year inflation in 2021 significantly higher than economists and industry analysts expected, investors are preoccupied with it for good reason. It can affect interest rates, private access to capital, and equity market valuations. In September, the U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI), a key gauge of inflation, pegged year-over-year inflation for August at 5.3%, still high but down from the previous month’s 5.4%. The Federal Reserve is targeting a 2% average inflation rate over the next few years.

That said, there tends to be misconceptions—and varying opinions—about the factors impacting inflation and the current levels. Client Focus caught up with Olga Bitel, global strategist with William Blair’s Investment Management team, to share her insights on today’s inflation numbers and what she is watching going forward. Bitel has nearly 20 years of experience analyzing macroeconomic and geopolitical developments to assess how global equity portfolios could be impacted. She has a B.A. in economics from the University of Chicago and an M.Sc. in economics from the London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Do you think the current inflation is transitory or is it expected to continue and potentially accelerate?

- While the year-over-year CPI is running 5%, month-on-month inflation figures have been falling for much of this year. In August, monthly inflation was down to 0.3%, versus 0.8% in April.

As supply chains have more time to adjust to demand with economies reopening following the COVID-19 lockdowns, and as the base effect wears off, we expect inflation to continue to decelerate sequentially. Base effect refers to comparing 2021 year-on-year data with 2020’s very low inflation numbers, which can skew readings. In May 2020, for instance, core inflation fell to 0.1%.

We are already starting to see some supply issues being resolved. For example, lumber prices made headlines in the spring when prices increased twofold from March to May. Today, lumber prices are already down 65% from May highs.

Persistent and accelerating inflation occurs when demand grows consistently more than supply. What follows directly out of this definition is that supply must somehow be constrained on a structural basis relative to demand for inflation to remain high, and/or rise beyond the reopening pains of post-COVID lockdowns.

COVID-19 lockdowns wreaked havoc with our extended supply chains and just-in-time inventory management. Many production facilities had to operate with fewer workers and limited hours. Ditto for transport and shipping. Carmakers canceled their orders for semiconductors, expecting demand to remain muted. Many employers in the services sector had to reduce their staff as customer traffic nearly came to a halt.

While the supply side was running with significant capacity constraints, demand for durable goods—TVs, computers, electronics, furniture—spiked as most consumers were spending more time at home. And as vaccination rates increased and COVID cases fell in the spring, activity on the services side began to pick up rapidly as major economies reopened.

In the U.S., real retail sales surpassed pre-COVID levels in July of 2020, while industrial production did not reach pre-COVID levels until a year later. In Q2 2021 specifically, the largest drivers of CPI inflation were autos, energy, and other industries affected by reopening, such as restaurants, hotels, and airfares. Underlying Q2 2021 CPI inflation—excluding these categories most disrupted by the pandemic—was in line with the 25-year average. - Is today’s rise in inflation the same as the ‘70s?

- The experience with inflation in the 1970s bears no resemblance to what we are talking about today. We are all familiar with the oil price shocks of the 1970s. What is much less discussed is that we had at least 32 different prices of natural gas and several tiers for oil prices, which were in effect for a decade. Wages and price freezes introduced in 1971 were supposed to last for 90 days but dragged on for years. Severe price distortions were common in many industries. For example, the price of poultry was regulated but the price of grain was not. It became so unprofitable for farmers to raise chicks that they drowned them, resulting in severe poultry shortages and sky-high prices at the supermarket.

The disastrous inflationary environment in the 1970s resulted from massive government meddling to curb rising inflation that only exacerbated the economic situation. The policies succeeded only in arresting supply adjustments and nearly killed demand.

Today, we are in a completely different environment, with economic growth this year likely to be the strongest in decades. We are even seeing encouraging data on private investment, as COVID-related supply disruptions are being worked out and firms invest for the future. - Is there a benefit to stronger inflation?

- Yes, there could be provided it is tied to stronger economic growth. By stronger inflation, I’m talking about something in the 2%-3% range, basically a level that is consistent with price stability.

We have experienced a long stretch of declining inflation. As a consequence, interest rates have been moving lower for decades. The perennial question in policy circles and in the wider society is why. Besides the well discussed disinflationary effects of globalization, excessive concentration of income gains limits domestic demand and ultimately aggregate growth.

A paper released at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium this summer quantified how rising income inequality over many decades was largely responsible for structurally lower interest rates.

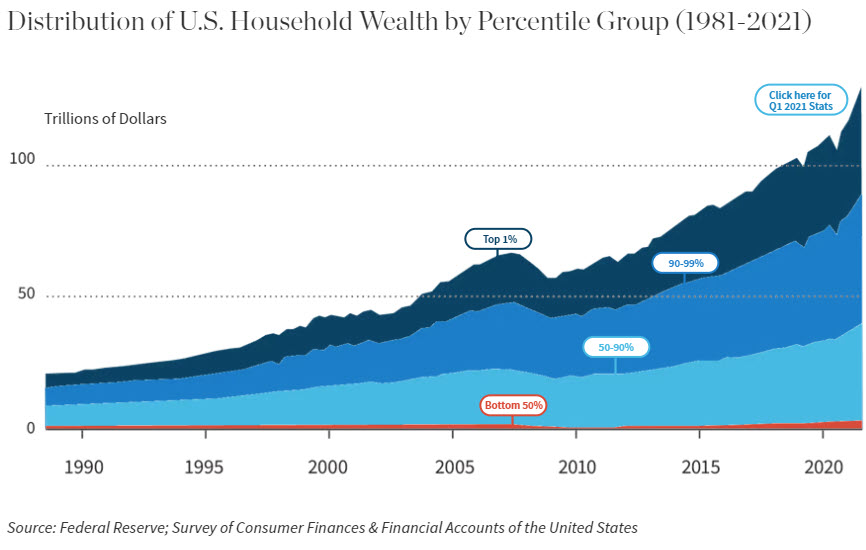

Middle- and lower-income families spend all of their earnings on everything from basic necessities to durable products, like cars, furniture, TVs, and services. In contrast, high earners are saving tremendous amounts because they just can’t spend it all. So instead of being used by the 90% to consume goods, a massive amount of wealth is going to savings. Over time, total domestic demand growth has slowed to a crawl.

Federal Reserve data show that the richest 10% of Americans held nearly 70% of the nation’s wealth in the first quarter of 2021, a record high.

- If Congress passes President Biden’s infrastructure plans, will that mean higher inflation?

- Not necessarily. If the plan is implemented gradually, it can increase our economy’s supply of human and goods capital, thus reducing inflationary pressures for a given rate of growth. But if there is a rush to build roads and improve infrastructure simultaneously across all states, the price of everything from basic materials to skilled construction workers will skyrocket. So, the plan needs to be introduced consistently and gradually to allow the supply of engineers, construction workers, and materials required to expand to meet that demand. There’s a nuance here. When demand and supply are balanced, inflation tends to stay low.

- What are you watching most closely to spot inflation red flags?

- The key indicators we closely follow are the monthly CPI report, purchasing manager surveys (PMIs), retail sales, and industrial production. As most inflation this year was driven by pandemic-related idiosyncrasies, we will continue to track to what extent they contribute to overall inflation. We continue to pay close attention to retail sales vs. industrial production to monitor the gap between demand and supply.