The outlook for world economies in 2023 has dimmed over recent months amid high inflation fueled by energy supply disruptions and the quick reaction of the Federal Reserve and other central banks to tame inflation by raising interest rates to levels not seen in decades.

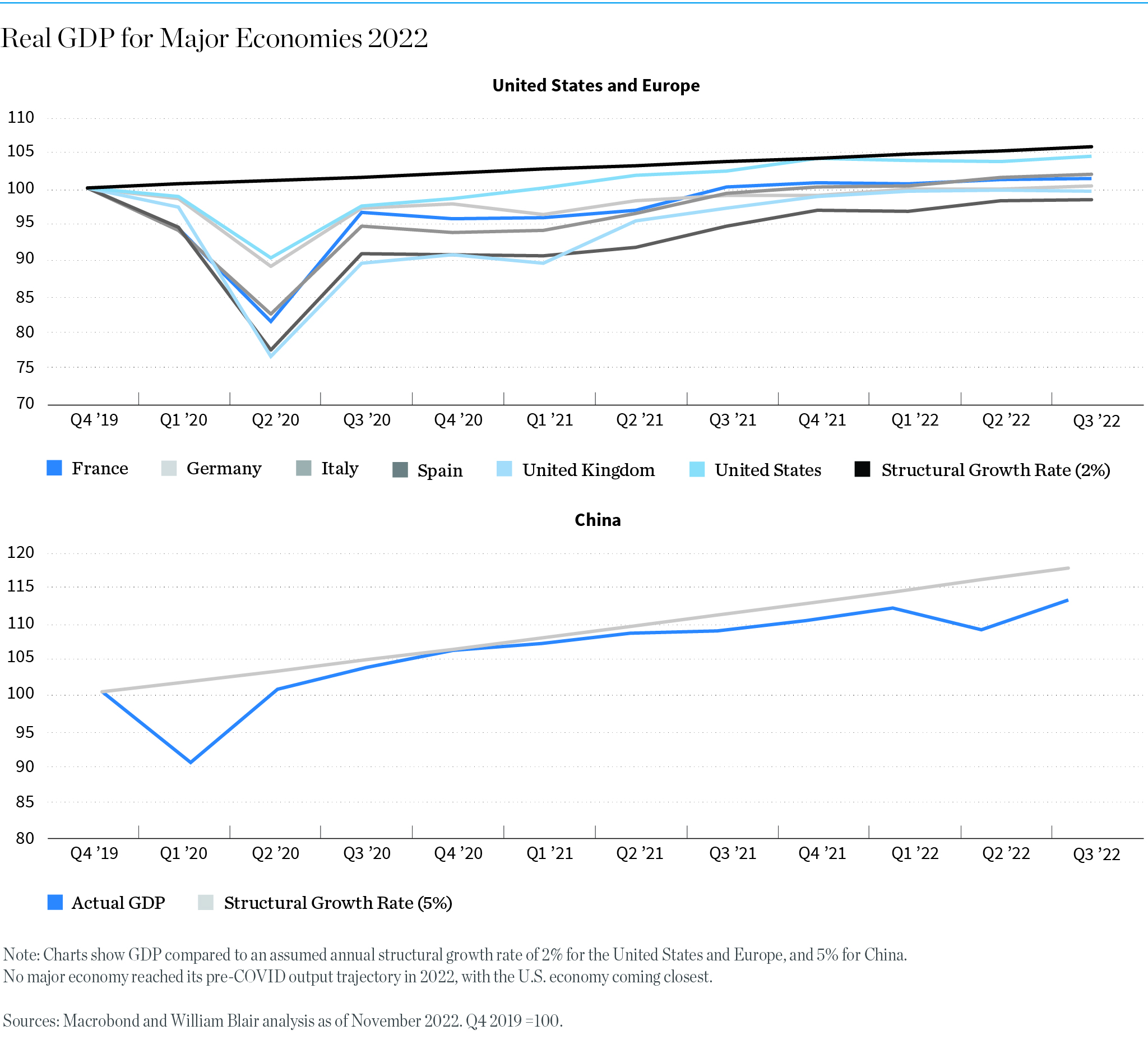

In the United States, the world’s largest economy, Fed economists’ median projection for 2023 real GDP growth is 0.5%, down from an earlier estimate 1.2% just three months earlier. That compares to an annualized increase of 2.9% in the third quarter of 2022 and 5.7% in 2021.

Given a variety of factors including high inflation, geopolitical turmoil, housing market weakness, possible supply chain disruptions, and over-tightening by the Fed to curb inflation, there is a growing possibility the U.S. economy could enter into a recession in 2023, says William Blair’s London-based macroeconomist Richard de Chazal.

“What is different about this expected economic downturn from the last few is that this recession is not being driven by a pandemic or a major financial collapse,” he says. “Rather, it would seem to be following the classic pattern of overly strong demand leading to higher inflation and a central bank that has to step in to bring inflation back down.

“As the Fed attempts to cool excess demand, two main implications of its response are that this slowdown is likely to be much slower than in the past, and it is not likely to be countered with an immediate burst of quantitative easing to support financial markets.”

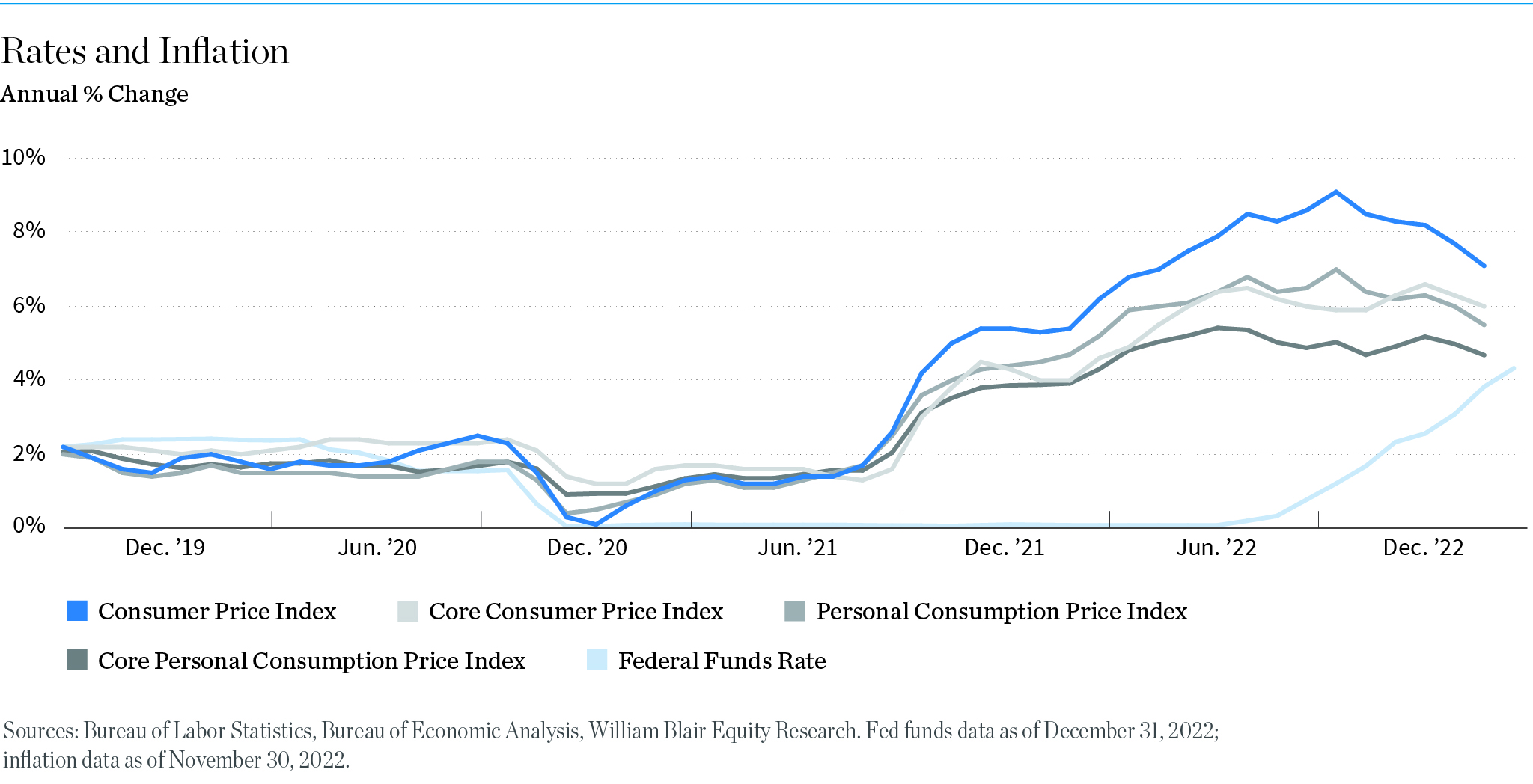

During 2022, the Federal Reserve has raised its benchmark interest rate 4.25%. That puts the current fed funds rate in the 4.25%-4.5% range, still quite low by historical standards. But given the Russia-Ukraine war is fueling inflation, which began in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Fed has indicated more hikes are possible over the next year.

Currently, the Fed is expecting to raise its benchmark interest rate to between 5.1%-5.4% in 2023, whereas the market expects the fed funds rate to rise to just below 5% by June 2023 before the Fed stops raising rates.

Growth Depends on Inflation

Analysts agree that economic growth in 2023 will largely depend on the pace at which inflation subsides. The U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI), a key gauge of inflation, continues to point to strong inflationary pressures across the economy. But there are some signs of it easing.

In November, CPI was up 7.1% from a year ago. Still high but moderating from its peak of 9.1% a few months earlier. It was also the smallest jump of 2022—one indication that higher interest rates are beginning to impact consumer demand. Note: The latest CPI numbers were released on January 12. U.S. inflation rose 6.5% in December.

“Since the second half of 2022, housing and rental prices, continued improvement in supply chains, and domestic wage gains all point to moderation in annual inflation,” says William Blair’s Olga Bitel, global strategist with William Blair Investment Management. “There are mounting reasons to believe that annual inflation of 3% toward the end of 2023 is attainable.”

Within the housing and shelter sector, which accounts for nearly 40% of the CPI, sales of new builds have fallen to the 2017-2019 average, Bitel says, while existing homes sales are at decade lows as 30-year fixed-rate mortgage rates passed 5% and 6%. The prices of goods, which grew strongly during the pandemic, have benefited from improvements in supply chains and have seen steady declines since last February.

“As we enter 2023, the spot price of a typical 40-foot shipping container is down some 70% from peak, purchasing manager surveys point to input price normalization, and suppliers’ delivery times are within reach of 2018-2019 averages,” Bitel adds.

Volatility to Remain Heightened

Since the Fed began raising interest rates in March and its quantitative tightening in June, much of 2022 was about financial markets realigning their expectations about just how much of an economic slowdown we can expect to have in the year ahead, de Chazal says.

“As a result, we have already seen a sharp reaction in financial markets, soon followed by a marked deterioration in those parts of the real economy that are at the forefront of interest rate sensitivity such as housing and autos,” he adds. “Looking forward to 2023, the economy will be moving into the next phase of the interest rate cycle, whereby other sectors of the economy will also start to come under pressure—including retail sales and business investment as well as corporate profit margins and employment.”

Volatility is likely to remain heightened in the coming year as the market assesses whether or not it has already factored in expectations of slowed growth.

“Encouragingly, some areas of the market have started to look more attractive, including smaller-cap quality stocks, which have historically tended to outperform from early in recessions and currently are more attractively valued,” says de Chazal.