Introduction: Is This Year Different?

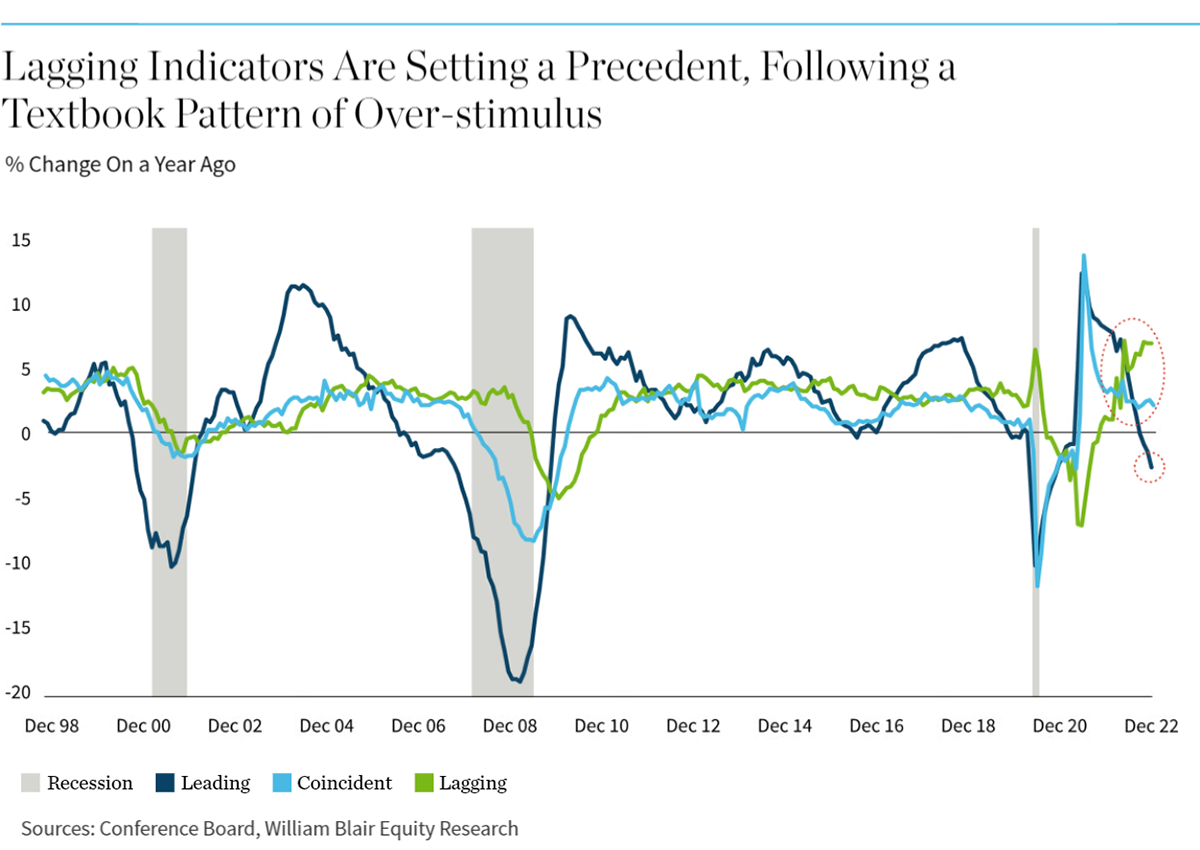

For a while now, it has felt like the U.S. economy has been stuck in the twilight zone. We have seen the leading indicators of economic growth deteriorating; however, the coincident and lagging indicators are still showing a significant amount of momentum, as shown below.

The main reason for this seemingly slow deterioration in growth is that this economic slowdown is not coming as a result of a sudden pandemic or financial market crisis—i.e., one that requires a quick cutting of rates and quantitative easing. Rather, the economy is following the textbook pattern of having been overstimulated, resulting in excess demand that is rubbing up against supply-side capacity constraints, causing prices to rise. This then forces the central banks to step in and tighten monetary policy to break the cycle and weaken growth by enough to drive down inflation to, once again, align demand with supply. And, as Milton Friedman told us, monetary policy tends to act with long and variable lags, with the result that this process takes time and is necessarily dependent on the time-varying sensitivities of each economic sector to higher interest rates.

Nevertheless, economic prospects are dimming. High inflation itself is already taking a toll on consumers, and we know that the cumulative impact of the medicine against such inflation—higher interest rates—will ultimately achieve its desired goal. We just do not know exactly how long and how deep the slowdown will need to be to achieve that goal, and whether something else will break in the process.

The prevailing mood, therefore, is still one of uncertainty about exactly what is ultimately to be revealed, and such uncertainty can itself become self-fulfilling as economic actors delay activity while awaiting greater clarity into new investment and spending initiatives. Only adding to this are the risks of geopolitical events, such as the war in Ukraine, the related energy crisis (and our fiscal response to it), and an emerging cold war with China around technology and security, and Taiwan. We also have the wildcard of what happens to global demand (in particular energy prices) should China eventually decide to reopen its economy.

In our view, financial market participants have already priced in a significant amount of downside around the expected deterioration of growth in corporate profitability, and much of the performance in 2023 will likely be related to “The Great Reveal.”

That is to say that as the year progresses, investors will be assessing whether the actual earnings and economic data meets, beats, or disappoints relative to those previous expectations, a process that will entail further market volatility as positions are then tweaked relative to the new emerging earnings picture.

Three Macro Factors to Keep an Eye on

1. The Consumer: As Good as it Gets?

The reality is that taking a still-life snapshot of U.S. consumers at the moment reveals them to be in exceptionally good shape and exhibiting almost all of the attributes any policymaker would normally dream of achieving in their policy decisions. A tight labor market (with unemployment at an exceptionally low 3.7%), strong balance sheets (as measured by the lowest level of debt-to-GDP since the early 80s), and high levels of savings means many consumers are in relatively good shape to weather the inflation storm for at least the near future.

However, we will be keeping an eye on consumer confidence, housing activity, and the cyclical shift from discretionary-to-staples consumption, all of which are showing signs of declining to varying degrees heading into 2023. We are also monitoring what these trends will mean for future corporate earnings.

2. Inflation: Back to the Future?

With relatively strong consumer and corporate fundamentals, inflation is unfortunately still very much the party wrecker. But with the Fed now swiftly draining the punch bowl, inflation is expected to continue to improve over the coming year.

While no two episodes will perfectly match, one of the most compelling parallels to today’s inflation environment is the period from 1946 to 1948. Prices then surged to 20% on the back of very strong pent-up demand following the war, as well as ongoing supply shortages and rationing, the elimination of price controls, and a central bank that was still being constrained in its ability to raise interest rates. During the 1970s inflation episode, however, the Fed was also late in draining the punch bowl, by which time inflationary expectations had already soared, labor unions were aggressively enforcing cost of living adjustments (COLAs) in wage negotiations, and inflation was much stickier.

Today’s policymakers, faced with similar pent-up demand and supply constraints following the pandemic, are this time around armed with more data, better gauges of inflationary expectations (a key driver of inflation), and the power to raise rates as much as they see fit. The result is that they can, and have been able to, respond in a much faster manner than was the case back then.

Hence today, while the CPI index at 7.7% in October is still far too high, we see growing evidence that it will continue to recede in 2023 to the 3%-4% rate by year-end.

On the supply side, we continue to hear talk of a growing supply glut of, for example, semiconductors; container freight prices are fully back to pre-COVID levels; and the New York Fed’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Index has also just about returned to pre-COVID levels.

Meanwhile, on the demand side, we are already seeing a contraction in the money supply growth for only the second time in history. And consumer spending is already under pressure from higher food and energy costs, sapping away purchasing power and damaging confidence. Meanwhile, the cumulative impact of continuing rate hikes is already being felt across various parts of the economy—the most significant here being the high-multiplier housing and autos sectors; this impact will continue through to the less-interest-rate-sensitive areas of the economy in the coming months and quarters.

3. Monetary Policy: Just as it Reads on the Label

Once again, what is notably different about this expected coming recession from the last three is that it is not being driven by a pandemic or a collapse in the financial markets, but by rising interest rates pushing down growth as the Fed attempts to cool excess demand, with two of the main implications being that this slowdown is likely to be much slower than in the past, and it is also not likely to be countered with an immediate burst of QE to support financial markets.

The Fed also clearly recognizes that not all sectors of the economy respond to higher rates in unison, given that different sectors of the economy hold varying degrees of rate sensitivity. From this perspective, the Fed should be quite happy to see that monetary policy is by no means broken and seems to be working exactly as intended.

For example, we can see that the economy has already passed through stage 1 of the tightening cycle: rising interest rates have already adversely affected financial markets, and we are also seeing a sharp reaction from the most interest-rate-sensitive sectors of the economy—autos and housing.

There is also tangible evidence that we are now slowly moving into stage 2, which, in the coming year, is likely to include weaker corporate profits, slower retail sales, and softer business investment. Ultimately, this cyclical margin pressure will lead to companies being forced to reduce costs by cutting employment and reducing wages. All of this should then help drive inflation lower.

The key for the Fed now will be to strike a delicate balance. It needs to go slow enough so as to not “break something,” which could then lead to the nightmare scenario of having to restart QE to re-liquefy impaired markets while simultaneously still not having achieved its inflation goal (this is effectively the situation that the Bank of England has been wrestling with in the last few months). But the Fed also still needs to increase rates at a fast enough pace to ensure longer-term inflationary expectations remain well anchored—something that did not happen in either the 1940s or the 1970s inflationary episodes.

One near-term problem the Fed has on its hands, however, is the degree to which financial market participants are overly keen to preempt the eventual policy “pivot.” The great irony at the moment is that the more the market believes in a pivot and eases financial conditions accordingly, the less likely such a pivot becomes if it makes the Fed’s job that much harder by dampening the transmission channel of monetary policy, at a time when inflation is still far from being fully contained.

This is exactly what took place this past summer with a strong market rally from June to mid-August and is seemingly happening again now following the release of the more moderate CPI Report. The Fed pays very close attention to this data, and this summer’s easing of conditions was one of the main catalysts behind the more hawkish Jackson Hole speech from Chair Powell. It would not be a surprise, therefore, to see the Fed hanging on to a hawkish view to quell the market push for the pivot.

Closing Thoughts on the Outlook for 2023

In our view, the U.S. economy has not yet entered a recession, although most leading economic indicators show that there is a growing probability that it will enter one in the coming quarters. What is different about this expected economic downturn from the last few is that this recession is not being driven by a pandemic or major financial market collapse.

Rather, it would seem to be following the classic pattern of overly strong demand leading to higher inflation and a central bank that has to step in to bring inflation back down. With the Fed having begun tightening in March, much of 2022 was about financial market participants realigning their expectations about just how much of an economic slowdown we can expect to have.

As a result, we have already seen a sharp reaction in financial markets, soon followed by a marked deterioration in those parts of the real economy that are at the forefront of interest rate sensitivity. Looking forward to 2023, the economy will be moving into the next phase of the interest rate cycle, whereby other sectors of the economy also start to come under pressure—including retail sales and business investment, as well as corporate profit margins and employment.

While financial markets already have made some significant downgrades in their future growth expectations and the bulk of the weakness is likely behind us, we should still expect to see heightened volatility around “the great reveal”—that is, the assessment as to whether they have discounted too much, too little, or just the right amount, as growth slows.

Encouragingly, some areas of the market have started to look more attractive, including smaller-cap quality stocks, which have historically tended to outperform from early in recessions and currently are more attractively valued. We are also entering the third year of the presidential cycle, one where the stock market has a strong history of outperforming other years in the cycle.